It’s interesting and a bit unfortunate to watch the battle currently raging over communicating science. This battle has now devolved into a false battle between truth and persuasion, as though they're mutually exclusive.

It's possible and desirable to use smart communication and accurate persuasion to build public support and acceptance of science, and to strengthen the role of science in public policy. I'm amazed that so many scientists don't wanna go there.

The truth vs. persuasion battle has turned into a

shouting match (see post and comments), as scientists, communicators, and communication scientists debate the

best way to respond to the anti-evolution and anti-science movie that opened last week,

Expelled (No Intelligence Allowed). Many scientists want to

debunk the movie and leave it at that. They seem to believe that it’s

wrong to do anything other than speak the truth and hope for the best.

This is most obvious in the science blogosphere, where most science bloggers seem to be wrapped around the axle of truth.

Their version of defending truth has put us in the position of ignoring other needs such as winning hearts and minds. And truth, by itself, is only a weak approach to winning hearts and minds, no matter how much science bloggers may wish it to be otherwise. Hoping to change that is a quixotic struggle, with a misguided motivation.

Why do some defend this version of truth so vehemently? It seems that too many scientists view defending truth as the be-all and end-all of being a scientist. Any other task is wrong and beneath us. Who cares if we can build support for science by being persuasive, because that would be an illegitimate success.

What is the relationship between defending truth and being persuasive? Are they really at odds, as many scientists seem to believe? No. It's possible to be accurate AND persuasive. That's the challenge in front of us, and too few seem to recognize that. Several who have tried to point this out are getting attacked, including Matt Nisbet, Chris Mooney, and Randy Olson.

Why do many scientists seem to believe that truth and persuasion are at odds? That's a tough question, and here's my suggestion for an answer.

Most scientists cling too tightly to our preferred method (simple truth statements) because we’re afraid of the slippery slope of trying to persuade. We fear that trying to persuade means accepting that “the end justifies the means.”

But if we use the science of communication, we can be persuasive while still being accurate. If nothing else, we can select what is persuasive from a list of different simple truth statements. Or, if it’s not too scary, we can actually build persuasive materials that are also true. We can parse carefully in communication science, just like we all parse carefully within our specialties.

It’s strange that most of us can split hairs so finely in our specialties, but bluntly refuse to engage in or even tolerate such fine distinctions when we get outside of our specialties. This problem seems to be rooted in how we’re trained and how we get comfortable with certain approaches and tools.

To succeed as scientists, we’re forced to get really, really good at parsing ideas and data in our specialties, and it’s hard to get there. But that’s where success resides, so that’s where we all aim. It works. But what happens when we seek to go outside of that comfort zone?

Outside of our specialties, life gets challenging. Either we’re babes in the woods with little expertise, or we take the risk of using comfortable approaches in a new field where they’re relatively untested. Success may follow, but mistakes should not be a surprise.

How does this apply to anti-science outreach like Expelled? Debunking is an adequate response within scientific endeavors, but it’s only a partial response to Expelled. Relying on debunking alone is misapplying a particular scientific approach. To supplement debunking, we need lots of accurate and engaging outreach that speaks well to large, diverse audiences. We need more movies like Randy Olson’s Flock of Dodos. And they need to be fun, not just crotchety attacks on the products of others.

Persuasion has the goal of getting people to change their minds, and simply stating the truth (like debunking Expelled) is one possible approach that may not be maximally effective. However, stating the truth is the preferred method of scientists, and dropping the method is unacceptable even if it’s persuasive. It’s a clash of goal vs. method and there’s no right answer. Overemphasis of either can turn into a major stumble.

It’s not ok to lie to persuade people that evolution is real, and scientists are justifiably worried about this risk (the worry that the end justifies the means). But many scientists fail to notice that we can make another important error if we cling too tightly to simple truth statements because we’re afraid of the slippery slope of trying to persuade. We can end up indirectly encouraging people to believe in intelligent design, because we’re unwilling to buckle down and learn the science of communication and use it in service of accurate persuasion.

In case you wonder why I feel capable of speaking to this subject...my thoughts come from my experience as a trained scientist and subsequent experience as a communicator and persuader. I learned science successfully, published two papers in Science as a first author from my thesis research, and got a tenure-track professor job. Thus, I believe that I know the science side of this very well. Subsequently, I quit academia and I’ve spent the last 15 years learning how to do conservation work. I’ve learned a lot about persuasion in that time, and it was a long, hard learning process. Not unlike my science training. Others like Randy Olson have similar tales of dual training, science and persuasion. And experts like Matt Nisbet pursue the science of communication and have a lot to teach us if we’re willing to listen.

It’s interesting and ironic to see so many scientists get so worked up regarding the false battle between truth and persuasion. If you take the time to get fluent in both, I think you’ll see that there’s really no problem. We can be truthful persuaders and do a much better job of building support for science and strengthening the role of science in public policy. And we don't need to be afraid of the slippery slope that heads downhill to spin and lying.

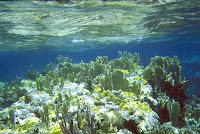

Will our oceans get hammered by climate change? Is it true that corals are already being harmed by climate change? The US Congress wants to know, and decided to ask a panel of experts in a hearing today.

Will our oceans get hammered by climate change? Is it true that corals are already being harmed by climate change? The US Congress wants to know, and decided to ask a panel of experts in a hearing today.