When is a wild salmon not really wild? When it's raised for part of it's life in a

fish farm called a hatchery.

Those so-called wild salmon you enjoy eating might have been fertilized in a bucket, then hatched in a tray and grown in a concrete pond for a year or more before being released into the ocean.

It's a dirty little secret of the "wild" salmon industry that the difference between some so-called "wild" salmon and "farmed" salmon is really just a matter of degree. Numbers vary with region and salmon species, but

anywhere from 40% to 90% or more of so-called "wild" salmon come from salmon hatcheries that are essentially large-scale fish farms. The numbers are lowest in Alaska and higher in Washington, Oregon and California. For some species, notably chinook and sockeye from Alaska, it's likely (but not certain) that a fish called "wild" has never been inside of a bucket, tray, tank, or pond.

This is not the same problem as

the mislabeling of farmed salmon as wild salmon. Hatchery fish are actually considered to be wild fish by all seafood standards currently in place, and hatchery-raised fish are considered to be wild fish by all seafood standards currently in place.

Definitive numbers are not available, but

about 80% of west coast "wild" salmon from major rivers come from hatcheries.

Even in Alaska, hatchery fish can be 70% or more of the catch of so-called "wild" salmon. So for many if not most salmon, a fish called "wild" has probably spent a major part of it's life in captivity being fed by people. Sort of blurs the distinction between wild and farmed fish, doesn't it?

Why should we care? Several reasons, including the

huge price premium for "wild" salmon based on claims of health benefits, better taste and texture, lower environmental harm, and sustainability. If those benefits are only real for fish that have NEVER been in a fish farm, then you are being deceived. But if those benefits accrue during the last half of a salmon's life, then maybe it's ok to call a fish wild even if it was produced and raised in a hatchery.

Some evidence shows that

young fish become contaminated during short periods exposed to toxic chemicals, so even a grow-out period in the ocean doesn't ensure fish are clean and healthy. Such problems loom even larger now that the

melamine pet food scandal has spread to farmed and hatchery-raised salmon.

Many

fishing guides believe strongly that hatchery life breeds salmon (or their cousins, steelhead) that are more like livestock than real wild fish, including my North Umpqua mentor Frank Moore, the world-renowned guide who first noticed the inferiority of North Umpqua hatchery steelhead. Sometimes, reeling in a hatchery fish is like a dead weight when compared to a robust and fiery fish that is truly wild, spawned in a river and never touched by a human.

What exactly is a "hatchery?" In general, hatcheries kill adult fish, mix their eggs and sperm in buckets, raise the eggs in trays until they swim, and then raise fish for up to 2 years in tanks or concrete ponds until they are ready to go to sea. The salmon then begin the wild portion of their lives in the ocean for 1-4 years until they return to freshwater to spawn (or get caught).

Thus, a "wild" salmon may live half its life in a pond and the next half swimming in the open ocean, compared to a "farmed" salmon that lives half its life in a pond and the next half in an open-ocean net pen. When in captivity, the "wild" and "farmed" salmon are in nearly identical conditions.

It's true that a year or more swimming free in the ocean is a significant difference. But is it enough to justify the whopping judgment of superiority given to "wild" salmon, even if they were spawned, hatched, and raised for part of their in a fish farm?

Decide for yourself. One thing is certain, the world of salmon is a lot more complicated than just wild vs. farmed. Hatchery fish that are called "wild" are somewhere in between these two extremes of wild and farmed, and nobody really knows whether hatchery salmon are more like farmed salmon or more like real wild salmon. Also certain is that if you eat so-called "wild" salmon you have probably paid wild fish prices (

up to twice as high as farmed salmon or more) for fish that were spawned in a bucket and did some hard time in a concrete pond.

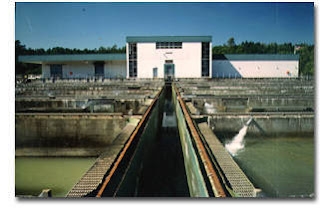

Image: hatchery where so-called "wild" fish get their start